November is the killing month. Animals have fed on the summer's bounty and the land won't sustain them all through the winter. It's time to thin down to breeding stock and anything which needs to grow for a second season. It's part of the cycle of seasons which rules our lives since we have chosen to live off the land.

So, in the last month I have sent a pig to the abattoir and helped butcher it, sent 4 Shetland sheep off, prepared 20 pheasants and 6 partridges, learned to dispatch, skin, gut and butcher a rabbit, been to a smallholders meeting about preparing chicken and curing bacon and hams and today I helped kill two of my sheep. Now, to many all this will seem unthinkable.

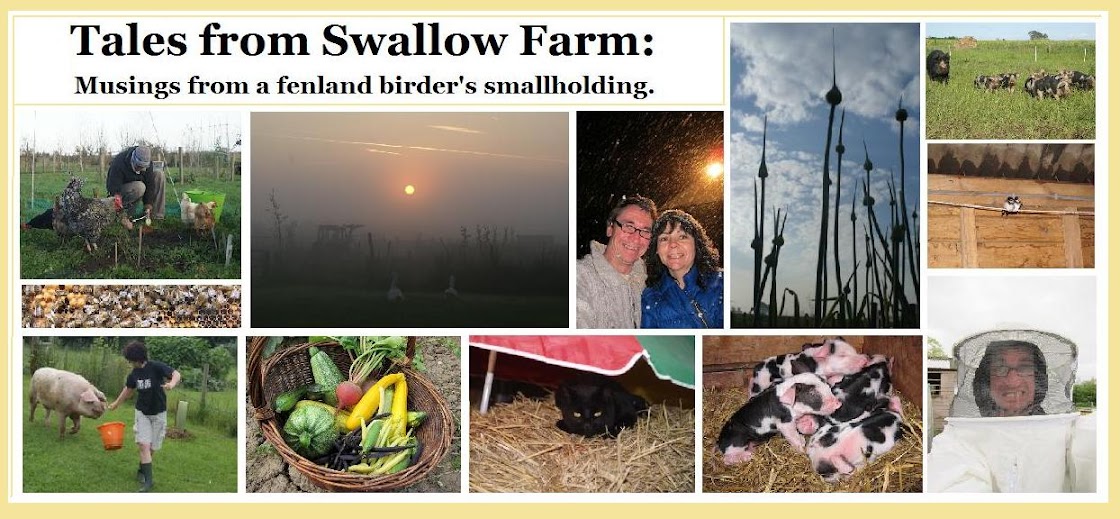

I always knew that I would reach this stage but it has been a journey which I would like to explain. And don't worry. I'm not going for shock tactics with the photos, though there will be some images near the end. If you're feeling uncomfortable with what you're reading then probably best not go any further! You don't need to come on the whole journey with me, but hopefully it will be interesting for anybody starting out in smallholding or thinking about it.

After all, it is all too easy to breed stock and end up with too many animals. Right from the outset you need to be clear what the animals are for and have a clear plan for 'the end' - that means waving goodbye to them, selecting an abattoir if appropriate, transporting them, filling in the paperwork, cutting the meat and having a plan for what happens to all the meat in the end. If your plan is vague, it's best not to let your animals breed, for you will end up with either a farm full of pet animals growing all too large and consuming a lot of expensive food or you will end up with freezers full of meat which you cannot possibly consume. Believe me, I speak from experience.

|

They may look cute at this stage,

but don't lose sight of why you're breeding your animals.

Otherwise you'll get more stock than you can look after, which is not fair on anybody. |

Someone I know says that you should either keep and kill your own animals or you should be a vegan and that anything in between is not a viable position. I don't 100% agree but do see where they are coming from. It may surprise you that I did actually used to be a vegan. I do believe that if you are going to eat meat then you need to face up to where it comes from and how it is reared. You need to reject mass production methods.

Smallholding and self-sufficiency sounds very idealistic and maybe idyllic. But it is hard work, not that I mind, and the smallholding side is not about keeping pets.

Even with something as cosy as keeping chickens, you soon come across the harsh realities of life and death. However well you care for birds, sooner or later one will become ill and you need to know what to do with it - and we're not talking an expensive visit to the vets here!

Then comes the point when you just can't resist allowing one of your broody hens to hatch out a clutch of eggs. It's all very cute until the chicks grow up and half of them (sod's law actually means it's normally more than half) turn into violent young cockerels fighting for alpha male position. The number of Facebook posts I see from people wanting 'loving homes' for unwanted cockerels, usually with names.

|

| There comes a point when the cockerels have to be dealt with. |

As a smallholder, I like to think that I raise my animals more humanely and more naturally than mass-produced livestock. But at the end of the day my guinea fowl, turkeys, geese, chickens, sheep and pigs are there for a reason and most of them will end up as meat.

And this is where we get to the nitty gritty of smallholding, the hard facts.

A pig or a sheep is fairly straightforward. You load it into the trailer one morning and drive it off to the abattoir, where you lead it into quite a nice little pen and then drive off. You don't need to know what happens next. It just gets returned to you neatly cut and packaged into joints. The most stressful part is probably getting it into the trailer in the first place, especially with pigs. My only advice it to come up with some sort of plan, give yourself time, be patient and, most importantly, be prepared to see the funny side of it when all goes wrong!

|

| One of our Shetlands returned from the butcher. |

The next step up the ladder, for most, comes with learning how to dispatch poultry. The killing, plucking and eviscerating (gutting) is the bit you don't have to do when you buy a chicken from the supermarket. You don't have to see the head or feet either. But most people are quite quick to get used to this, in the knowledge that their chickens have had a good life. You can still opt to send the chickens off to be 'dealt with', but this becomes a significant cost compared to the cost of rearing the bird. Probably only worth it for a turkey or a goose, or if you're selling the meat.

But there comes a stage when you end up with something which approximates the whole chicken you would buy in a supermarket or at a butchers. After that, most meat eaters would not baulk at what might be classed as the first steps in butchery, jointing the chicken.

The next step in our journey dealing with meat came with a friend offering us game birds left over from a shoot. A couple of weeks ago I was kindly given ten brace of pheasants. I was going to write a blog post called pheasants for the peasants, but I never quite got round to it!

Sue and I learned how to skin the pheasants from YouTube a couple of years ago. It's surprisingly easy. You don't even need to pluck the birds and you can get the breast and legs off without going anywhere near the insides. To be honest there's virtually no other useful meat anyway. This method is so quick that I managed to process all 20 pheasants I was given the other day in just a couple of hours.

From chickens and game birds, the next step up was last year's Christmas turkey - well, we actually ate it about February! I don't really do Christmas.

The broomstick method of poultry dispatch (no, we don't chase them round and round the yard with a broomstick) has made Sue and I very confident in dong the deed. Once you can do a chicken, there's not a lot different doing other birds. They're just slightly larger or slightly smaller.

So the journey so far has taken us from sending off our sheep and pigs to actually doing the deed and all the subsequent preparation ourselves with poultry.

But for me the biggest step is when it comes to dealing with mammals rather than birds. I sort of did these in the wrong order. I started by going on a pig butchery day a couple of years back. It was way too complicated, not helped by being led by a good butcher, but not a good teacher.

A step backwards came last year when I picked up Daisy's carcass from the abattoir and drove it over to the good people at Cambridgeshire Self Sufficiency Group to be used for a sausage making demonstration.

|

| Fond memories of Daisy... but the sausages were lovely too |

I spent a day helping (aka getting in the way) Paul cut up and package our pig. I've never really struggled with sending animals to the abattoir. No tears have been shed, however much I respect the animals during their lives. I didn't struggle with picking up our sow either, even though she was very friendly to me and was still recognisable when the carcass came back.

You may think me heartless, or perhaps think I've become desensitised to all this. Yes, I've gradually got used to it, but I have never lost my care or respect for the animals. I am just matter of fact about it. Sue and I still say sorry to the animals before they go.

The next step was when our sheep went off last year. They made very disappointing weights, but we learned lessons and this year we were delighted with the weights which our Shetlands made.

Anyway, we had volunteered a couple of last year's sheep for a Fenland Smallholders Club lamb butchery day. Unfortunately in the end the carcass was somewhat overchilled and chances for us to have a go were limited. However, it was another step in my learning. It seemed a lot less complicated than a pig and, with the help of Youtube to refresh my memory, I would be happy to have a go in the future.

|

| This year's pork when it still had a bit of growing left to do |

And so to this year's pig. We didn't raise it ourselves, as we've formed a co-op with a couple of other smallholders. This means that the pigs, sociable animals, can be reared in a group without us having mountains of meat on our hands. The butcher we used to use went downhill quite rapidly last year with the loss of a couple of staff members. We were no longer happy with their service. However, if you get the abattoir butchers to cut your animals, the sausages are made from all the pigs which go through the establishment that week. This kind of destroys the point of rearing your own rare-breeed animals.

And so we went back to the services of Paul, a private butcher. This meant taking the carcass over to his and helping with the butchery again. We have been very happy with the meat and the sausages. I learned a lot more this time. Even better, Paul was able to turn half of our pig into smoked bacon and hams which have proved absolutely irresistible.

Thus far, as far as mammals are concerned, I had managed to stay well away from the killing part of things (and the skinning and gutting).

But last week another smallholder was sending a litter of rabbits on their final journey and had volunteered to show other interested parties how to do it.

(This is the point where you may want to stop looking at the pictures if you're sensitive about this subject matter)

|

The transition from feathers to fur

certainly makes a difference

to how it feels |

So we headed down to Prickwillow in the heart of The Fens. Four furry rabbits were meeting their maker. I didn't actually do the deed on any of them. Sue tried but needed help. However, we did discover that the broomstick method worked even better on rabbits than it does on poultry! A karate chop to the back of the neck is another quick and efficient way.

|

| Saddle of rabbit x4 |

The rabbits were large-breed and it really did feel different to killing a bird. However, when it came to the skinning and preparation, I was surprised by how very similar it was to skinning a pheasant. The skinned and eviscerated carcass was remarkably similar to a large bird, just with an elongated section in the middle. The jointing was very simple too. In fact, rearing rabbits for meat is a strong possibility in the future. The meat is not as 'rustic' as wild rabbit and is very lean and low in cholesterol.

And so to today. A couple of my older Shetland sheep had served me well but needed to go now before the winter. For the first time I was planning on not sending them to the abattoir. Instead I was going to home kill. Well, to be more precise, Paul was going to home kill them for me. There are rules about this. Firstly the meat has to be solely for the consumption of the owner. Also they still need to be dispatched humanely, stunned first. I wasn't quite sure what to expect and approached the day with some degree of trepidation. But I felt that I owed it to my livestock to at least see what happens to them in their final moments. I feel this actually increases my respect for them when they are alive.

|

The ewe on the left and the wether below.

Both photos taken a while back. |

Without going into too much gory detail, the whole process was not as traumatic or as messy as I had imagined. I'm sure some of this came down to Paul's careful handling of the animals, both while alive and once dead.

|

| Bleeding out our Shetland wether |

Obviously the most shocking part is the stun gun, which is basically a bolt to the top of the head. This is quick, humane and all totally above board and within the rules. I was surprised by how instant it was. It actually pretty much always kills the animal outright anyway. The next bit which I was dreading was the slitting of the throat to drain the blood. However, Paul was quick with a knife through the neck and the animals just slowly bled. The most disconcerting thing was that, just as with a bird (and the rabbits did this too) the muscles still keep on twitching so the animal is still kicking and twitching for quite a while. But rest assured, it absolutely is 100% dead.

The skinning was fascinating. This is the part where the walking, living animal which you once looked after suddenly starts to look much more like meat. Again, the process was remarkably similar to skinning a bird. It just needed a bit more effort. Paul was remarkably skilled at this and left virtually no residue on the skins.

Finally we were on to the gutting. If you've ever experienced the smell when a chicken is gutted, you'll understand just how little my nose was looking forward to this! However, Paul's careful knife work ensured that there was no leakage and the intestines and other bits came out remarkably cleanly. They went into a bin bag for disposal (more rules).

And that was that. The carcasses, as they most definitely were by now, were left to hang overnight. It would have been easier for me to get Paul to cut the meat on the same day and take it away, but I hadn't realised that before the fat 'sets' the whole carcass is remarkable wobbly. This means that any attempts at preparing the meat inevitably end up with difficult, messy cuts.

So I returned on Monday morning. Paul had already pretty much finished one sheep and had the pair of them finished in no time at all. I was really pleased with the finished product. One of the sheep had been an old girl who, although appearing very healthy, had steadfastly refused to put on any weight. I thought we'd just get a few scraps of mutton off her, but in the end she gave us some very nice cuts of meat.

The good thing about getting Paul to butcher our animals s that you get everything back. The bones can be used for the dogs, or for stock. The spare fat can be rendered down for the wild birds (with a pig, the flare fat makes a wonderful product called leaf lard). The liver, fresh as fresh can be, makes for a delicious treat. I am learning how to make tasty treats out of some of the other offal too. Again, I feel that out of respect for our animals we should use every part of the body if we possibly can.

So this time I planned to make proper use of the hearts -I have eaten these before, but just fried them up to see what they were like. This time I followed a YouTube recipe by the wonderful Scott Rae.

Here is the link and, despite our doubts, it really did make a tasty, nutritious meal.

As a little side dish, we had crispy lamb's tongue. You wouldn't usually get this back form the butchers, so I was keen to give it a try. To be honest, it wasn't too bad but I wouldn't call it a delicacy. I'll try it again though, or I'm quite sure that Boris and Arthur would not turn their noses up!

As for the skins, I would have loved to have turned them into sheepskin rugs for us but Sue and I just don't have enough time for this at the moment. It's quite a lengthy process. You also need a licence to do this, so of course we would not have tried it even if we did have the time. But we knew a friend who was very keen to take them off our hands. It will be fascinating to see the finished product.

|

| Salting a sheepskin |

So that's it. My journey from vegan to butcher! Well done if you've stayed with me the whole time and good luck if you're thinking about embarking on a similar journey. My best advice would be to find someone who can show you how to do everything properly and to never lose respect for your livestock.